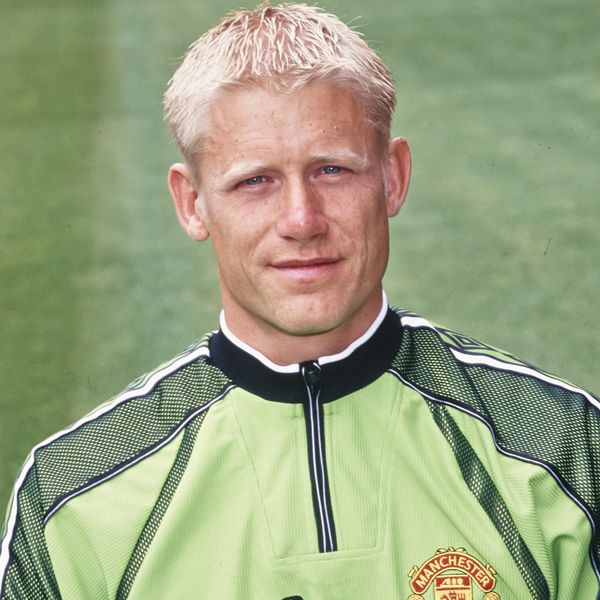

Schmeichel recalls Treble success in new book

Manchester United’s incredible 1998/99 season had that fairytale ending at the Nou Camp and featured games of unforgettable drama at the Stadio delle Alpi, San Siro, Villa Park and, of course, Old Trafford. But who remembers Charlton away? Peter Schmeichel does, in this extract from his new autobiography, One...

Let me tell you about one dark, wintry afternoon at The Valley that may have held our best 90 minutes of 1998–99 – in a certain way.

There are games that characterise a football team. There are moments a campaign hinges on, even if nobody realises at the time. There are memories that stick in the brain long after seemingly bigger ones have faded and gone. Charlton away.

It was 31 January, a cold, dry and gloomy Sunday, a 4pm kick-off. We had spent a total of three days at the top of the league since the season began and arrived in south-east London sitting third. Charlton at The Valley was a tough fixture. They had a cautious, disciplined team, organised by a canny manager in Alan Curbishley, and nothing was happening for us in the game. I dislocated a finger and our doctor popped it back in, then it dislocated again. I signalled to the referee, who stopped play for a second time to allow the doc to repeat the procedure, except this time strap the hand up. The Valley was an older stadium, where the crowd always felt on top of you and the goalmouths were muddy. Charlton kept slogging towards their 0-0.

And then.

In the final minute, Gary Neville pumped a long diagonal into their box to set up a last attack. Charlton lumped clear. Gary returned the ball to Scholes, who shimmied into space and chipped to the far stick. Yorkey, with the most finely judged header, angled it home off the post. We went top and, apart from a fortnight in spring when Arsenal had played more games than us, would not relinquish that spot again.

We kept winning games in that mode, pushing to the end and finding the answers off the bench if we needed to, all the way to Barcelona.

It is in tough, unglamorous settings like a muddy goalmouth at the Valley on a dark January afternoon that titles are won. Apart from that, I only have really clear recall of a handful of other league games from 1998–99: a 2–2 at Anfield; Ole’s four goals coming off the bench in an 8–1 win against Nottingham Forest; a draw at Leeds; and the day we clinched the title, at home to Spurs. Those, plus our 3–2 defeat by Middlesbrough at Old Trafford on 19 December – our worst performance of the season and the very last game we lost.

I don’t know why we played a terrible game against Middlesbrough. In the dressing room afterwards we sat embarrassed, looking at the floor. Eventually eyes began to lift and we started talking. ‘How did we play so badly?’ From there it developed into a discussion, for the first time, about what we wanted from the season, what we were trying to achieve. The consensus was we had just not been good enough: we were eighteen league games in and there had been more draws and defeats than wins. We had to improve. We said, ‘Let’s just agree between us not to lose another game.’

From there grew a routine of which Yorkey was a very big part. After Middlesbrough somebody quipped, to laughter, ‘Thirty-one wins, and we’ll have an unbelievable season!’ and that started it. We would look at the number of games left , and someone – Yorkey usually – would chirp up with the comment. We beat Forest: ‘Thirty wins, boys!’ Then drew with Chelsea and beat Middlesbrough in the cup. ‘Twenty-eight wins!’ It seemed a bit of a joke initially, but it built and built and Yorkey loved the chat. After Charlton there he was, grinning. ‘Hey, boys . . . twenty-four wins!’

Charlton away – that was the week we showed what we were. Which was: relentless, positive to the last. You could challenge us with anything – the kick-off time, an early goal, ninety minutes of the toughest Premier League grind – and we would still come through. We weren’t going to break the commitment we’d made on 19 December, when there were still thirty-one (in the end it was thirty-three, because of FA Cup replays) games to go.

We beat Fulham in the next round of the cup and had Chelsea in the quarter-final. Di Matteo got sent off, Scholesy got sent off . We missed chances. A nil-nil. In the replay at Stamford Bridge we won 2–0 through a Yorke–Cole special and a sublime Yorkey finish.

Arsenal in the semi-final. We were neck and neck in the league and the build-up was all about our rivalry. Whoever wins the cup tie will win the league, the media said – and internally we shared that feeling. It went to a replay which began with Teddy holding off close markers and setting up David for a brilliant strike, and then you couldn’t take your eyes off the game. There were incidents everywhere. Seaman made an exceptional save from Ole, Dennis Bergkamp equalised via a deflection and I made a bad mistake, fumbling a shot for Nicolas Anelka to score – he was off side, thankfully.

Roy got red-carded for two bookings. Arsenal had the momentum. In stoppage time, Phil Neville tripped Ray Parlour – never our favourite player – and Bergkamp had a penalty to win it. In the moment, I did not understand that everything was on the line, there and then. I thought there were ten minutes left or something. I hadn’t seen the board for stoppage time go up. I thought that, even if Bergkamp scored, we would have time to chase an equaliser.

Bergkamp was a great footballer, but in that moment I did not care who he was. With penalties, I never thought about the taker, never researched what side he liked to put it and all that. My approach was to focus not on my opponent but on me: that way, I put myself in control, not them. I would make a clear decision about which way I was going to dive and stick to it, so that it was my call, my responsibility, about me. And there was my arrogance – or rather, the conscious way I used arrogance as a tool. Don’t look at the taker. Treat them like air. Act superior. Let them know: if you want to score against me, you have to be at your best. Bergkamp put the ball to the side where I was diving, at a nice height, and I pushed it away. Players came to congratulate me, but if you look at the footage I’m screaming at them to go away. Guys, guys, the ball is in play, get upfield. I was surprised when the ref blew for full time straight away. And so we plunged into extra time: the FA Cup and probably the Premier League, thirty minutes, us or them.

FA Cup semi-final replays were scrapped after 1999 and I think Andy Gray said in commentary that if Ryan Gigg’s winner was the last semi-final-replay goal we would ever see then so be it, because his goal will be up there with all the goals we talk about until the end of time. I had the perfect view. As soon as he collected Vieira’s stray pass in our own half, I could see something was happening. It was the way he ran, the purpose in his movements, the acceleration with which he set off – with Arsenal stretched.

It was a killer sniffing blood. Ryan bobbed past the first man, Lee Dixon, then wove past the second, the covering Vieira. Then when Dixon got back, Ryan went past him again. He left Martin Keown on his backside, then veered away from Tony Adams. We played with Mitre balls in the FA Cup, which weren’t great, and it was a bumpy pitch, yet Ryan just flew across the ground. Seaman was fantastic across the whole semi-final and beating him took something special. But Ryan just blasts it – over his head into the top of the net. What a goal. Crazy good. ‘Hey, boys . . . ten more wins!’

I never experienced a better atmosphere at Old Trafford. We had just been to the San Siro and I had never heard anything louder than the sound when Inter scored, but our fans took things beyond that level as they roared us on to chase Juventus down. The eruption of noise, when Ryan’s goal went in, I’ll remember for the rest of my life. For me, in terms of atmosphere, that game is the benchmark for big European nights at Old Trafford. On paper, 1–1 was a first-leg result that favoured them, but our feeling, coming off the pitch, was ‘We’ll do this.’

Inter, Arsenal, Juve - they might seem to be the best performances of the season. But I can’t get away from Charlton. You think about it: we won the Premier League by a single point from Arsenal. We don’t score that last-minute goal at The Valley and we don’t win the title. There is no Treble. Charlton 0 Manchester United 1 (Yorke 89) – it was not a high-profile victory, but it absolutely summed us up.

© Peter Schmeichel 2021. Extracted from One: My Autobiography by Peter Schmeichel, published by Hodder & Stoughton.